The importance of digital accessibility

Accessibility is something that should be baked into all digital strategies, and yet it receives very little resourcing and attention from organisations across the globe.

In fact, in February 2021, when WebAIM ran their annual accessibility analysis on the Majestic Millions list, they found an average of 51.4 errors per page — that’s a striking 51,379,694 errors in total.

97.4% of the homepages analysed had detectable WCAG 2 failures, spanning across six major categories including low contrast text, missing alternative text for images, missing form input labels, empty links, missing document language and empty buttons.

In a world where we‘re advocating so strongly for equality and seeking representation, we need to be doing the same in digital environments. And it all begins with education.

So… what is web accessibility?

At its core, web accessibility is about making your website or product usable by as many people as possible, ensuring that all users are treated the same, and are afforded equal opportunities, regardless of their abilities or circumstances.

And why is it important?

According to the World Health Organisation, over 1 billion people (around 15%) of the global population live with some kind of disability — that’s a substantial number of potential website/product users.

It’s important to remember that no two users of your website or product are the same —a user’s needs will differ from person to person, regardless of whether their impairments stem from a disability (be it visual, auditory, neurological, cognitive or motor) or from environmental factors.

While it may sound like there are a lot of different impairments, disabilities, or environmental factors that need to be catered for, it isn’t quite as intimidating as it sounds.

What steps can we take to improve accessibility?

Below, I’ve listed a series of quick and easy tips that will improve some aspects of your website or product’s accessibility. It’s not an exhaustive list, and it isn’t going to fix all accessibility issues, but it’s a good place to start.

Use descriptive alt text for images, links, videos and other types of media

Alt text, or alternative text, is used to assist screen readers in understanding content on any given page. This aids people using assistive technology, but will also work as a fallback if images aren’t found, and will also provide more context and descriptions to search engine crawlers.

When writing alt text, you’ll want to make it as descriptive as possible.

Using the image below as an example, writing something like “apple pie” won’t help users in understanding the context of the image. Whereas something like “single service of apple pie drizzled with honey” provides context around the image, and a stronger description.

You’ll want to steer clear of keeping the text blank, or filling the tag with a list of keywords related to the image.

Include subtitles and transcripts for audio/video

Subtitles and transcripts allow users with auditory impairments to have access to the information with audio and video media. They can also assist users who have been diagnosed with learning and cognitive disabilities, who might process information more easily when reading it.

A lot of voice recognition software can assist with generating captions automatically, but it’s important to note that more often than not, they will need editing.

It’s also important to include additional captions for things like unspoken words that might appear on the screen, as well as any important sounds such as music, laughter and noises, to assist in providing context to users.

Create descriptive text links

Screen readers and some other assistive technologies navigate websites from link to link, skipping the surrounding text. Because of this, it’s important to ensure that your link text makes sense out of context, steering clear from generic phrases like “read more” or “click here”.

An example of a bad text link: If you’re interested in learning more, click here.

When announced by a screen reader, it would read as “link: click here” — it provides no context for the user, and doesn’t indicate where it might take the user.

An example of a good text link: If you’re interested in learning more, read this article about link text.

In this example, when focussed, screen readers will announce “link: article about link text”. It provides users with more context, as well as what they can expect to find at that destination.

Consider colour usage

Colour usage is a broad and extensive topic when it comes to accessibility.

It can be broken down into a few sub topics, and is something I’ll definitely cover in a blog post of it’s own in the future.

Colour contrast

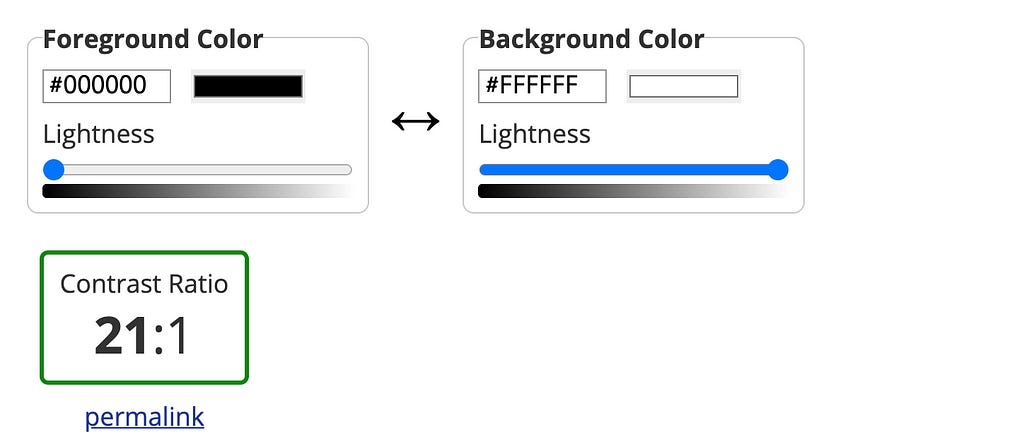

Colour contrast is measured by the difference in perceived ‘luminance’, or brightness, between two colours. The brightness difference between two colours is then expressed using a ratio, which ranges from 1:1 (white on white), to 21:1 (black on white).

For some additional context, I’ve included a screenshot below of WebAIM’s contrast checker.

The general rule of thumb is that any text and interactive elements should have enough contrast between the foreground and background colours. To meet WCAG 2.0 Level AA, the contrast ratio should be 4.5:1 at minimum, with large text (18.66px and larger when bold, or 24px and larger when regular) requiring a contrast ratio of at least 3:1.

There are certain exceptions to these contrast rules as well, some of which include: inactive elements, decorative elements, hidden text or skip links, unimportant text within an image and text within a logo.

WebAim have a great contrast checker tool which allows you to test your contrast ratio and visualise it alongside the WCAG requirements.

Colour indicators

Some users with visual impairments may have trouble differentiating between certain colours. For this reason, using colour alone to present instructions or meaningful content, such as error states, results in poor accessibility. It can be used to reinforce a point or status, but should never be the only indicator.

Be an advocate

One of the easiest things that anyone can do to improve accessibility is to be an advocate.

Fight for the user in your new project, listen to those around you, document why you’ve made certain design or development decisions, and educate your team when you see something that could be improved.

In the business of designing for users, we can’t cherry-pick which users we’re designing for based on pretty colour palettes, abstract font choices or innovative interactions.

We need to design for all users, push for digital inclusivity and bake accessibility into every design and development decision made along the way.

The importance of digital accessibility was originally published in Bootcamp on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.